The Nature of Tent Use in the English Civil Wars

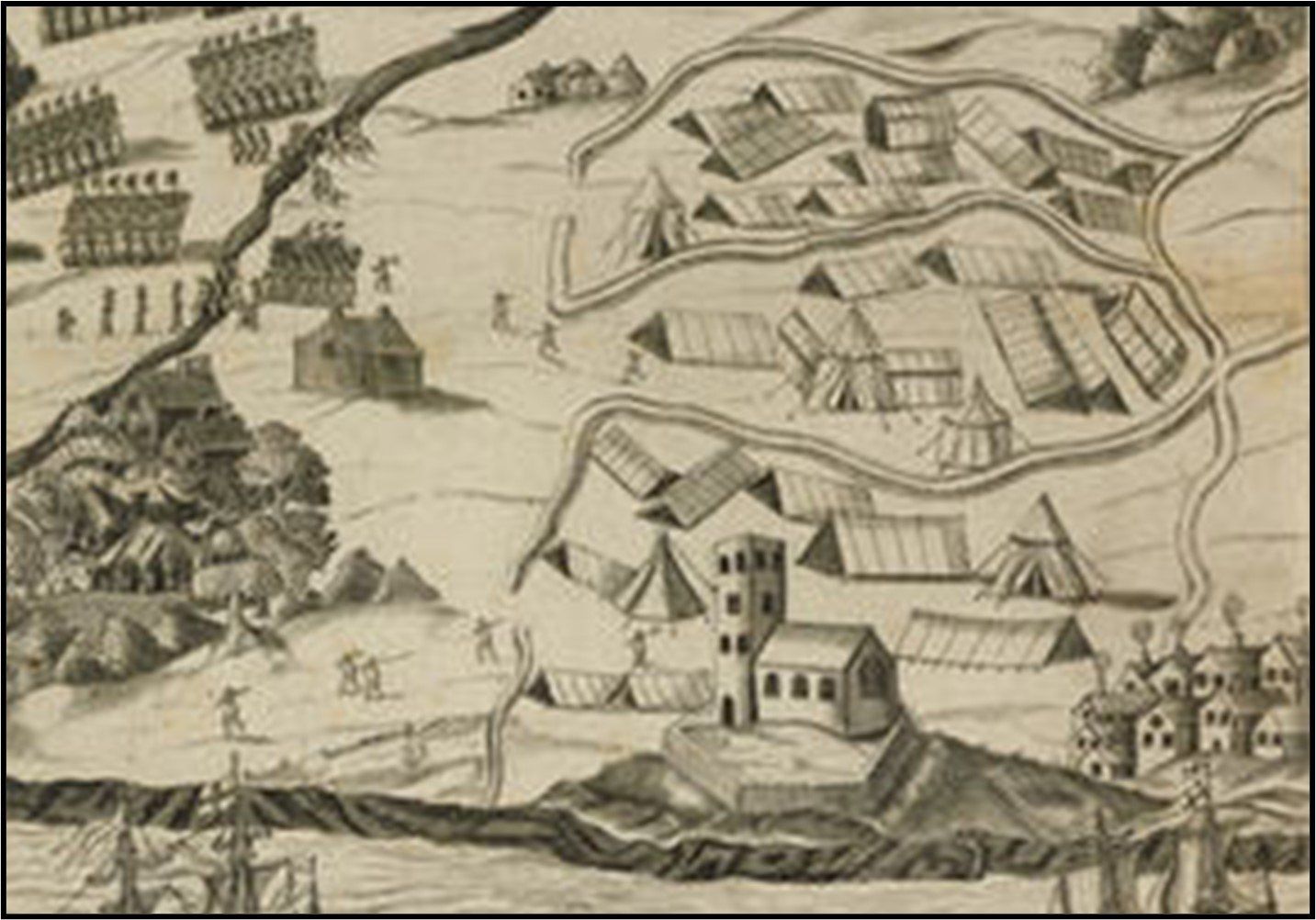

- There is occasional evidence for the use of tents by ordinary soldiers, but billeting in existing civilian buildings or purpose built huts was far more common.

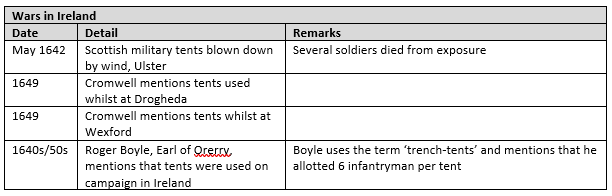

- Tents were normally the preserve of officers during the English Civil War. The use of tents by regular soldiers was much more common during the contemporary wars in Ireland and Scotland.

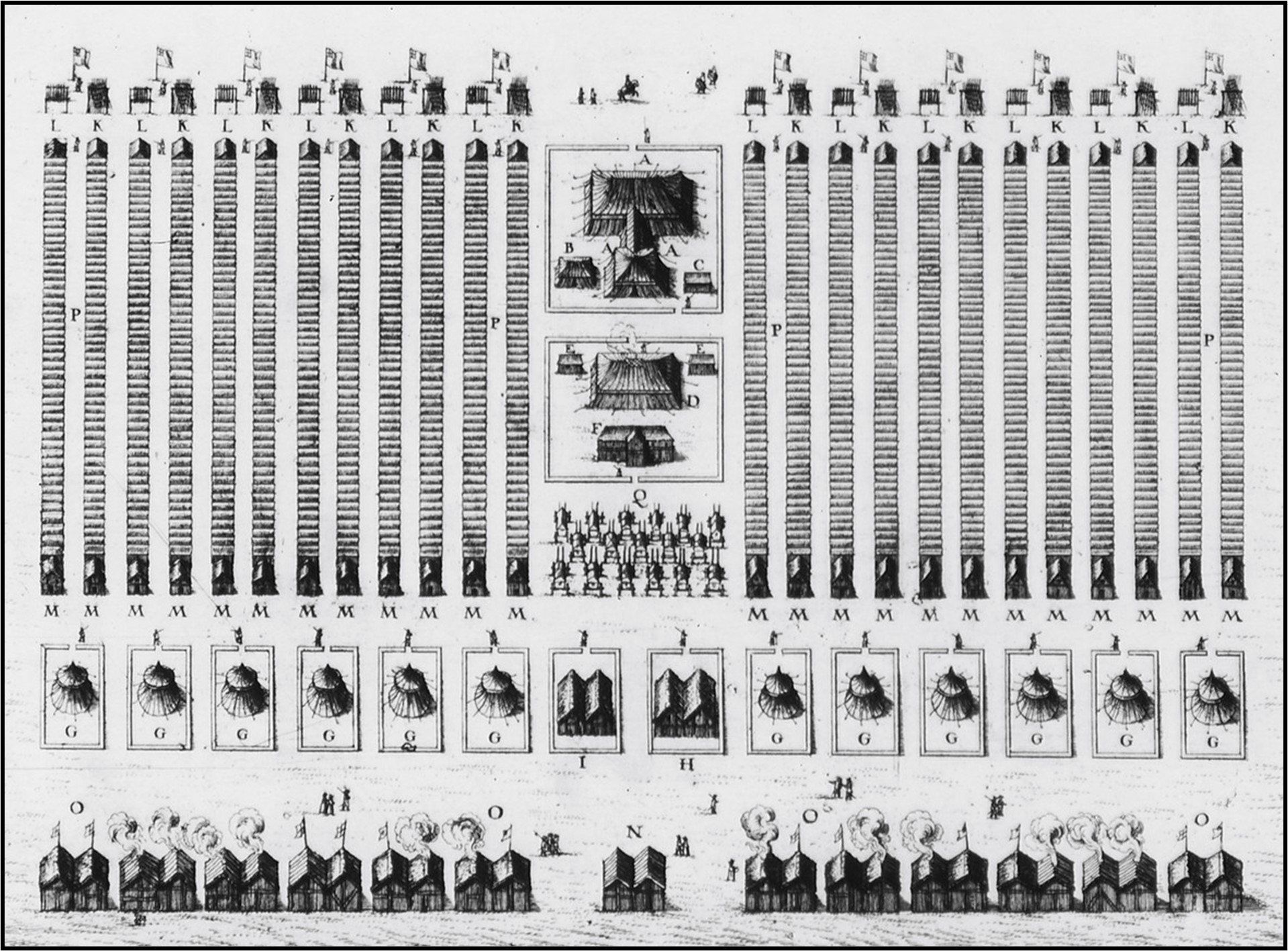

- Where tents were used en masse, they seem to have been made to a standard design: 7ft square and 6ft high, to accommodate a file of six soldiers.

- the tactical activity of the unit,

- coherent forward planning,

- the weather,

- the availability of civilian buildings,

- time available for setting up the camp, and time in place,

- availability of timber and thatch, and

- the immediacy of the threat posed by the adversary.

Who used Tents and When

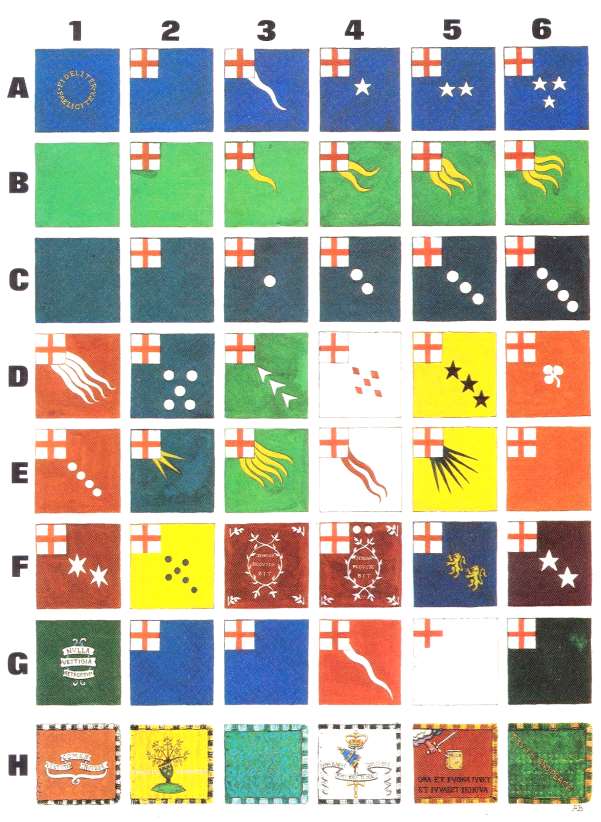

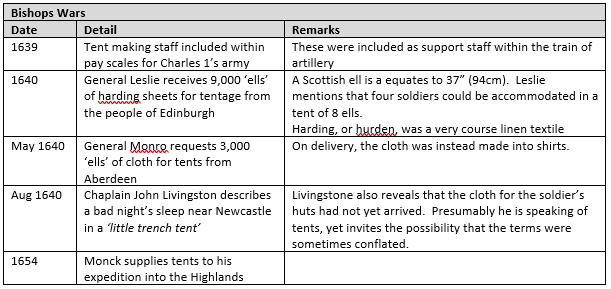

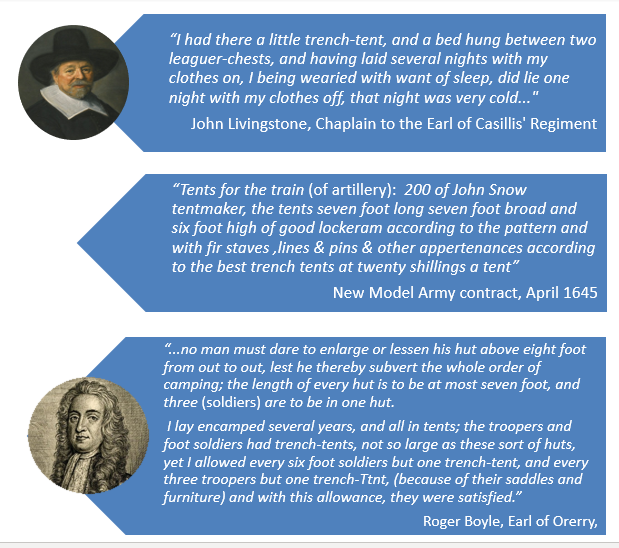

Tents were normally the preserve of officers, and sometimes for use within the train of artillery; however there are occasional mentions of tents in use by common soldiers. Most examples are for service in Scotland and Ireland, possibly a consequence of sparse settlement patterns and long marches. Available evidence for tent use in the British Isles during the 1640s-50s is as follows (drawn from Rowland):

Tents and Devereux’s Regiment

As a garrison unit, it seems highly unlikely that the original Devereux’s Regiment would have required tents. Much of their campaigning involved the defence and seizure of settlements and manor houses in Northern Wiltshire. We have ample evidence of billeting, and no evidence for the use of huts or tents.

Tents and Fairfax’s Regiment

The appearance of ‘trench tents’ within contracts for the artillery train of the New Model Army occurs as early as April 1645, although it is unlikely that tentage was employed widespread within the ranks of New Model until its campaigns in Scotland and Ireland. Cromwell made extensive use of tents in Ireland in 1649, although climactic sickness still made a heavy impact on the health of his forces.

Part Two: The Form and Fabric of Soldiers’ Tents

The ‘Trench Tent’, a Standard Form?

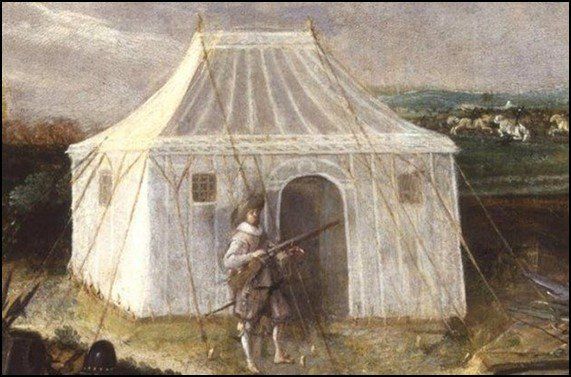

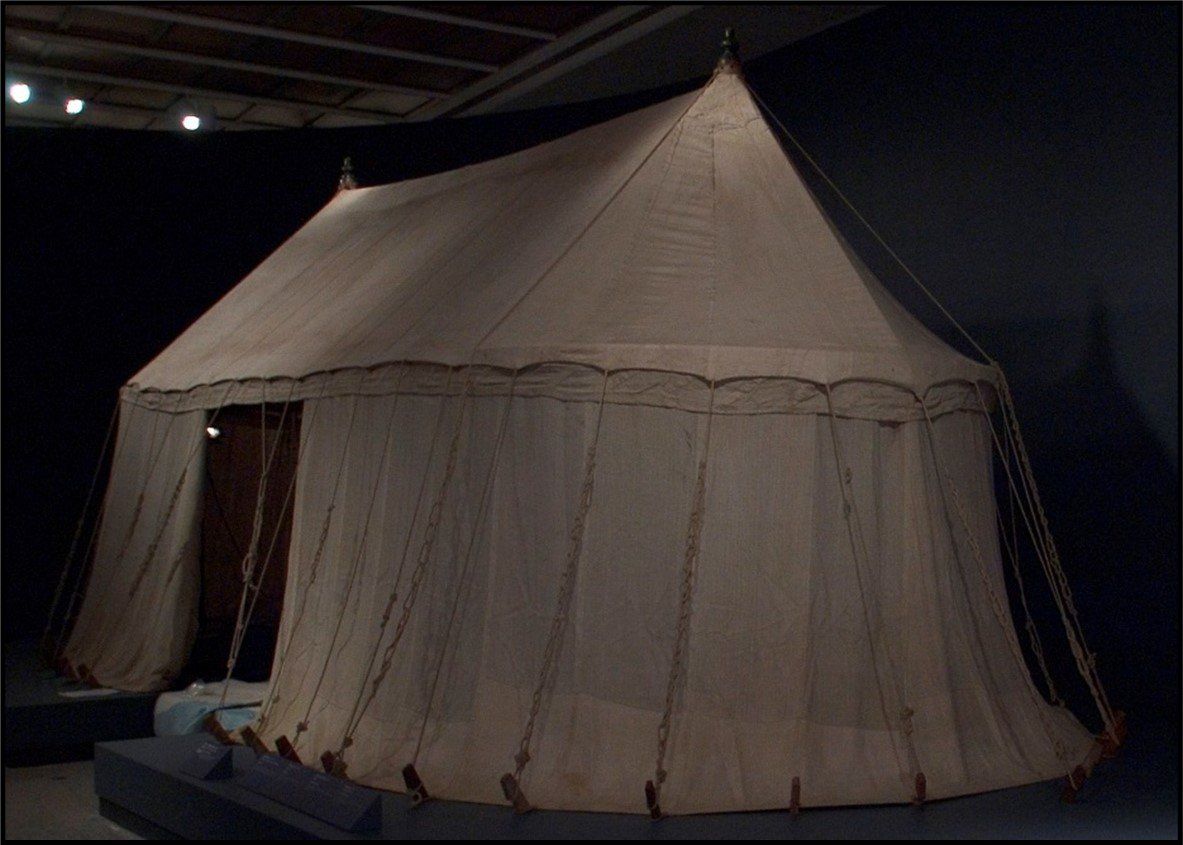

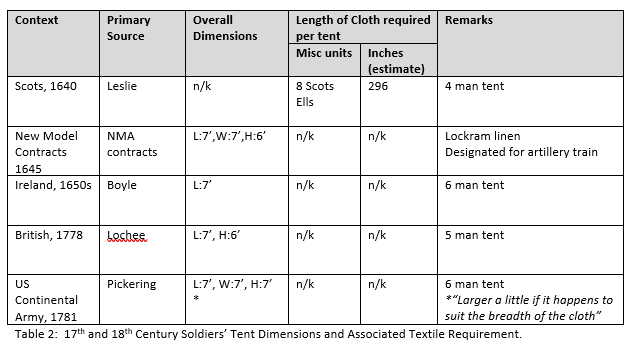

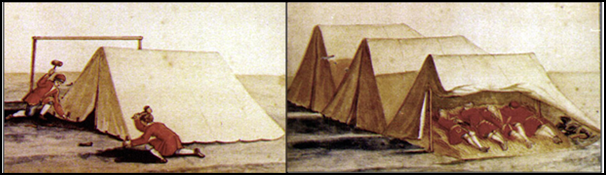

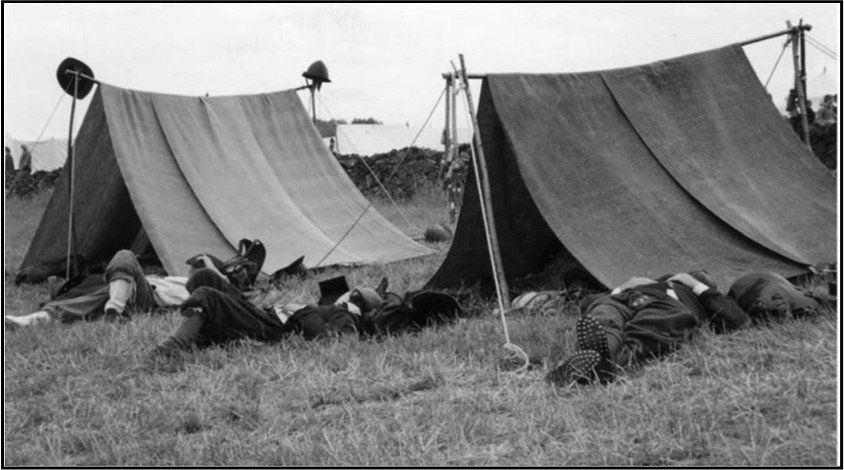

There are at least three separate references to ‘trench-tents’ in 17th century contexts, and where dimensions are detailed, both indicate a length of 7 feet. Remarkably, the New Model Army contracted trench tents are near identical in terms of outer dimensions to those the British Army were using in the latter 18th Century both in Britain and in North America (see Table 2). The only significant difference appears to be that the latter 18th century soldiers’ tents featured a curved end on the opposite side to the doorway, apparently used to deposit equipment (see Fig 9). Research has thus far failed to find an explanation for the term ‘trench-tent’, but given Boyle’s use of the term ‘entrenched encampments’ it may conceivably that the term is short for ‘entrenched-tents’, reflecting military-academic enthusiasm for entrenching campsites (which seldom appears to have been the reality).

Tent Flaps

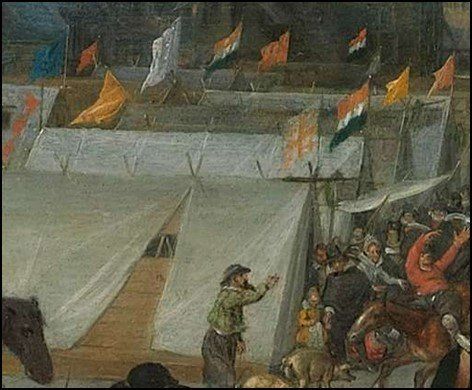

Unfortunately the New Model Army contract does not detail whether the tents were to have tent flaps. A cursory study of military scenes between the 16th and 18th centuries reveals numerous examples of tents with and without tent flaps. It is unclear from 17th century depictions how tent flaps were secured closed, although the Graz tent features wooden toggles on the tent flaps. This would explain the lack of dangly ties which can frequently be seen on living history tents. It is also possible that a doorway only featured at one end, similar to the British military tents of the 18th century. With respect to huts, Boyle simply states that: “Every company is to have the door or opening of every hut towards the lane, which is common to the said two files of huts.”

Fabric and Construction

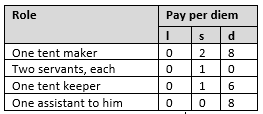

Tentmaking was a specialist craft, but as per Table 1, in desperate times bulk orders might be placed with generalist textile workers. The Royalist artillery train in Oxford in 1643 employed Roger Pickford and his son as tentmakers, whilst General Monck employed a tentmaker for his campaign in Scotland. The New Model contract of April 1645 went to one John Snow*. The daily pay established for tent-making specialists accompanying Charles I’s army of 1639 were as follows (Grose, p289):

*Probably not identifiable with either the curmudgeonly broadcaster or northern king of the same name.

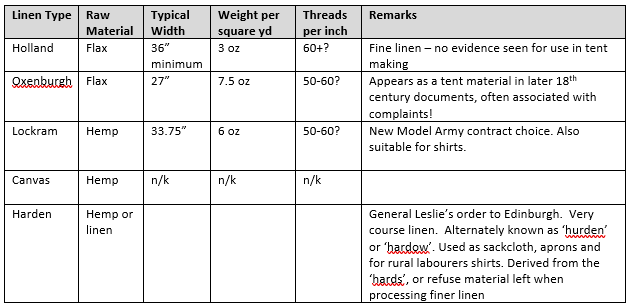

17th century tents appear to have been made from flax or hemp, both processed into linen. It is highly likely that tent makers retained the selvedge of the cloth. This would have resulted in a more robust edges and seams, whilst reducing the amount of labour time and wastage. Seams on the surviving examples from Graz and Basel are flat felled (see Fig 9), and it is likely that similar seams would have featured on soldiers tents. The Basel example also has blue-dyed linen strips sewn to cover the seams on the outside of the tent, although this level of frippery is unlikely for soldier issue tentage. The variation in cloth widths would likely have resulted in tents that were sometimes some inches outside the prescribed 7’ width and 7’ length. 17th century linen was manufactured in a range of widths, from 28” to 40”. Thus three panels of around 30” width could easily be sewn to a 7’ (84”) width, with sufficient allowance for seams. We should nonetheless remain alive to the possibility of narrower panels, which might be inferred from some period illustrations (see Fig 2).

It would appear that the linen chosen for tentage was variable, and sometimes the most expedient choice rather than the best available.

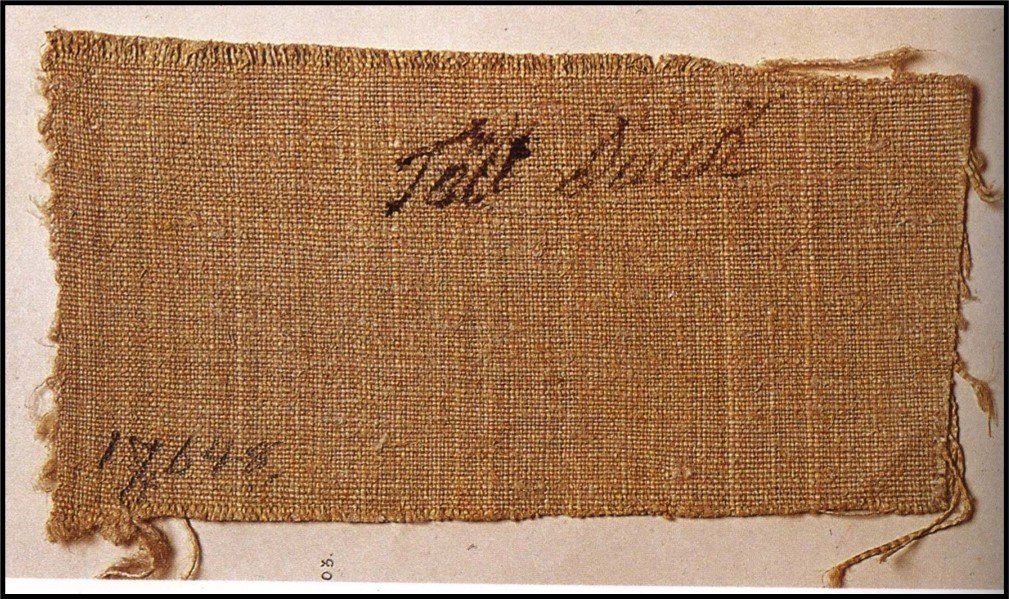

The New Model Army contracts state lockram as the preferred textile, which is of hemp rather than flax. Peachey describes the lockram’s width as 33.75”, which would work well for a three panel 7’ tent with generous seam allowance. It is unclear whether tent linen would have been bleached. Most period illustrations show an off-white colour, although a sample of 18th century tent linen is decidedly brown, as is one of the tents depicted by the 18th century artist David Morier. It seems highly likely that even where unbleached tents were issued, that moderate use would have seen the linen bleach in sunlight.

Framework and Furniture

The New Model Army contract sets the requirement for “firre staves lynes & pinns & other appurtenances”. Quite what “other appurtances” is open to the imagination, but likely to be pegs and possibly also bags. Equally incongruous is the mention of “firre staves”. As a softwood, pine seems entirely unsuited to an item which might undergo a considerable degree of strain on campaign, where the sole conceivable advantage would be its lightness. The framework for soldiers’ tents consistently appears as a simple goal post shape in period illustrations. An 18th century description provides a method for fixing the frame together:

“These tents are fixed by means of three poles and 13 pegs: the poles A are called standard poles, and are about 6 feet high; the pole B is called the ridge pole, and is about 7 feet long: the ridge and standard poles are held together by two iron pins, fixed in the top of the standard poles” (Lochee).

The iron pins here described are probably the pins mentioned in the New Model contract. Despite the mention of ‘lines’ in the contract, there are no visible guy ropes featuring on period illustrations of common soldiers tents. Instead, the frame is likely to have been held in place by ramming the posts into the ground, or else by the tension of the canvas once pegged to the ground. Although 17th century evidence for this is sparse, Wolf Huber’s depiction of the battle of Pavia, drawn c1530, depicts a freestanding goalpost arrangement, where the uprights have been rammed into the ground. The same arrangement is also shown in an early 18th century depiction of redcoats erecting tents (see Fig 10)

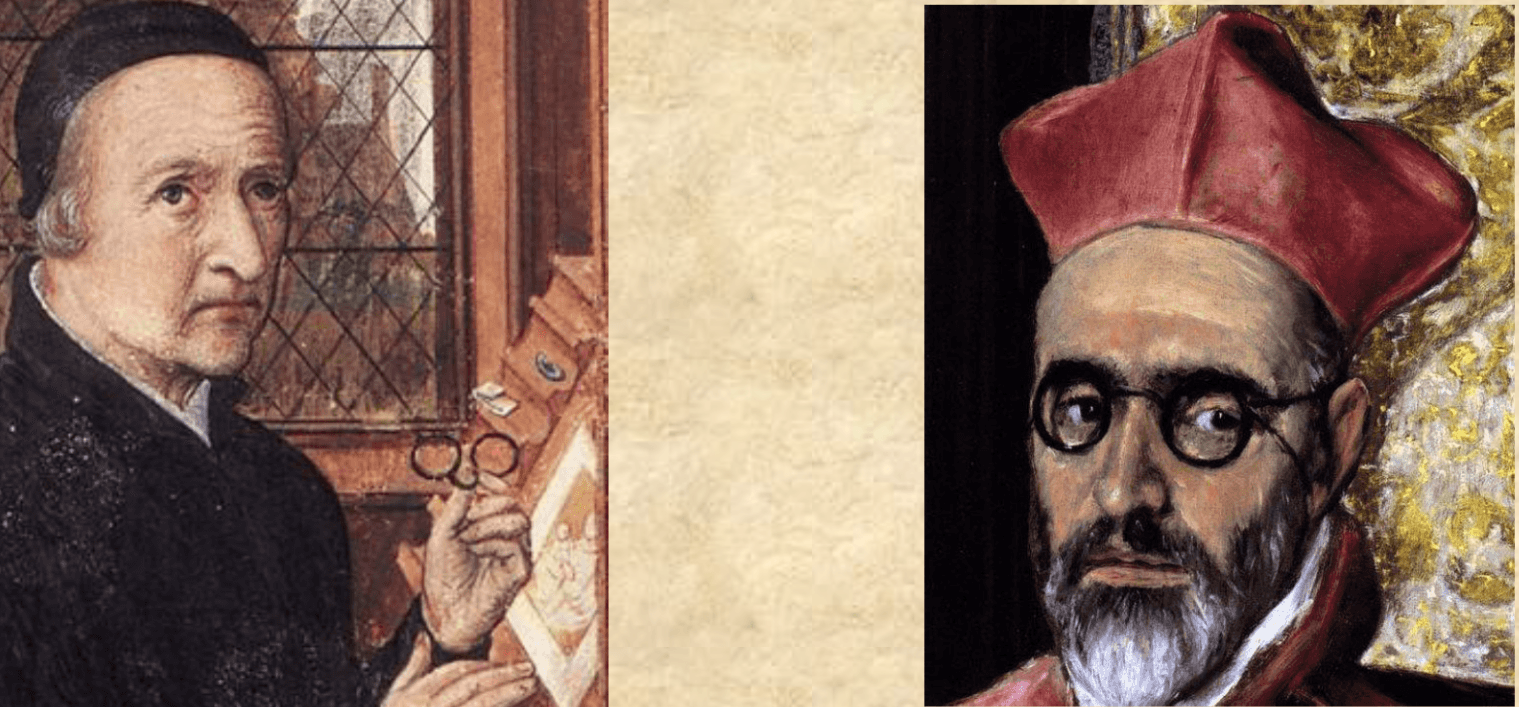

Pegging points on the Graz example were reinforced by an extra layer or linen and leather tabs. It is likely that there is also an internal grommet, through which a short length of rope would pass. This is possibly the same system as shown on the portrait of Sir Horace Vere (Fig 1). This system would allow the pegging to be adjusted on uneven ground, and replaced easily following wear and tear.

Further Work

Accepting that tent use was the exception rather than the norm during the ECW, it would nonetheless be an interesting project to attempt a tentative (pun intended) reconstruction of the New Model Army ‘trench-tent’. The broad dimensions and textile type is apparent in the April 1645 contract. Further constructional detail can be derived from surviving 17th century tents and the framework visible in early 18th century British military tent illustrations.

In the meantime – let’s keep our eyes peeled for more evidence!

Bibliography

- Boyle, R. (1677): A Treatise on the Art of War. London. Link

- Grose, F. (1786): Military Antiquities Respecting a History of the English Army. Link

- Livingstone, J (1727): A Brief Historical Relation of the Life of John Livingstone, Minister of the Gospel. Link

- Lochee, L. (1778): An Essay on Castramentation. Link

- Mclean, W. (2012): A Seventeenth Century Tent from the Armory at Graz. Link

- Miller, B. (2002): Ben’s Tarptent. Link

- Mullins et al. (2010): To Shelter the Enlisted Man: A Study of Other Ranks Tents during the American War of Independence. Link

- Peachey, S. (2014): Clothes of the Common People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England. Bristol, Stuart Press.

- Rowland, A.J. (1995): Military Encampments of the English Civil Wars. Bristol, Stuart Press.

- Ward, R. (1639): Animadversions of Warre.

- Website: Information on authentic Medieval Pavilions. Link