A Guide for members of Colonel Nicholas Devereux’s Regiment...

Introduction

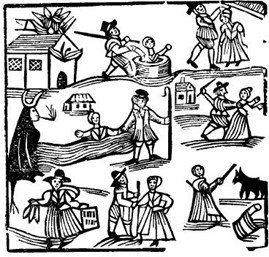

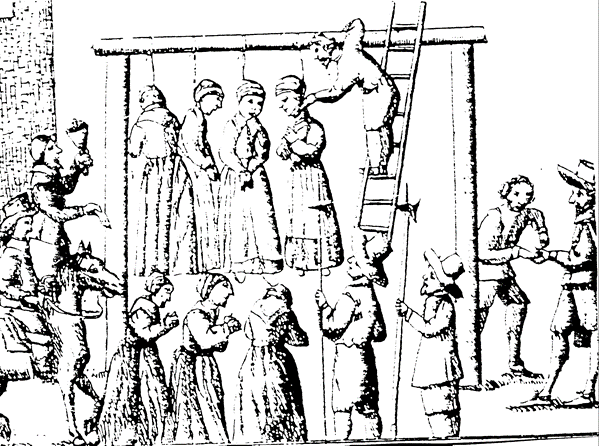

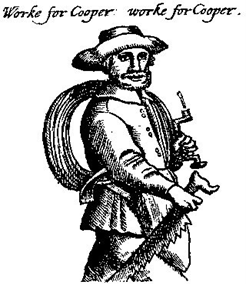

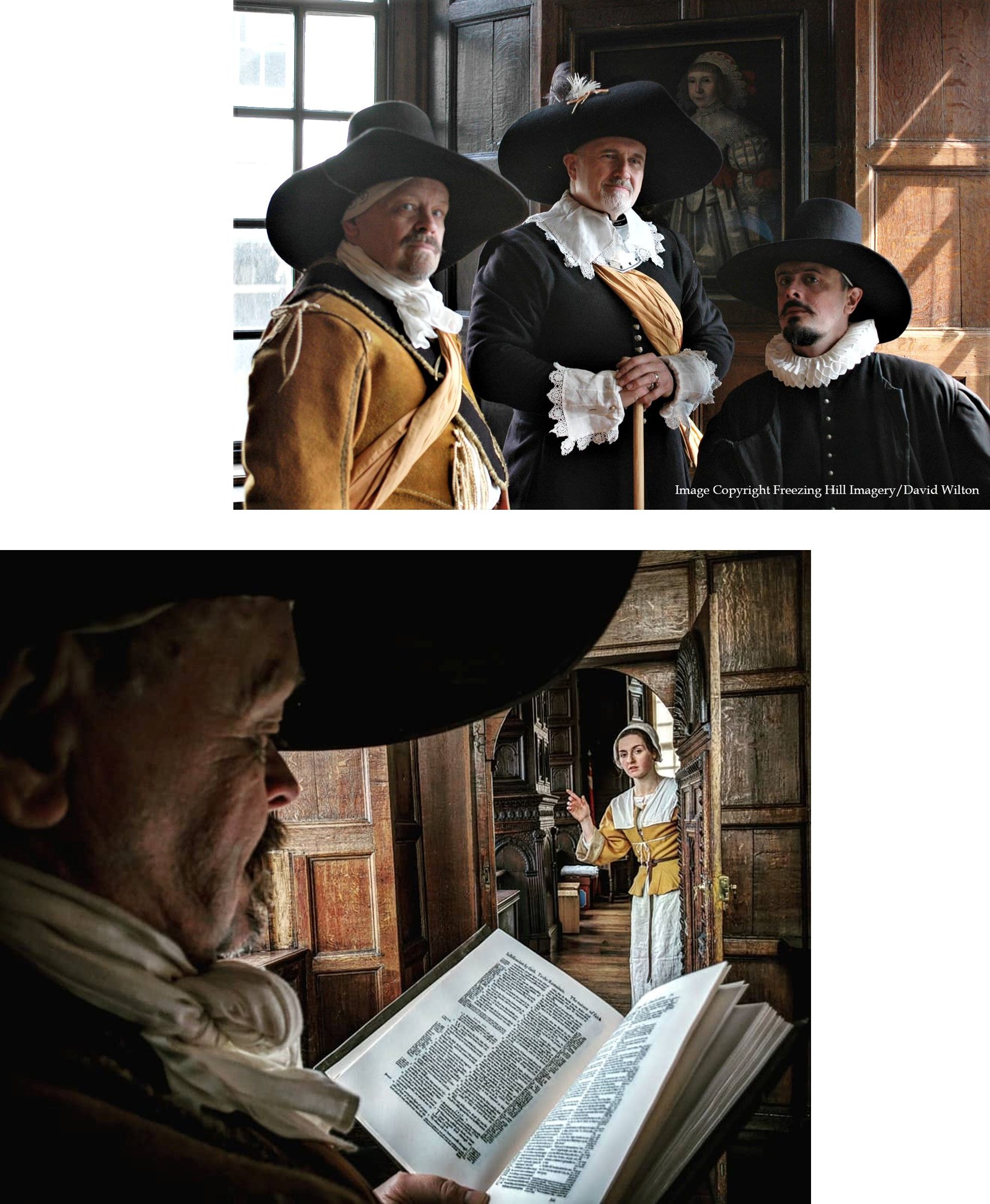

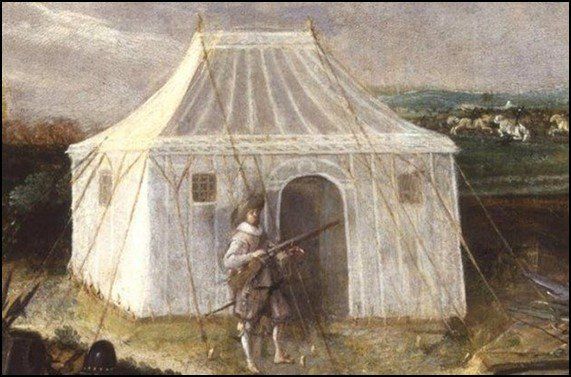

This is a guide designed to support new and existing members to produce a convincing representation of the clothing of the common people in the mid seventeenth century. It is written with the aim of supporting members with getting together a typical basic outfit that can then be developed further as expertise, interest and finances allow and involvement in the hobby grows. It is not intended as a great academic work covering every aspect of clothing of the period. Neither is it produced with the intention of being the definitive truth about what people wore in the period – the only way we will ever know for sure is by travelling back in time and seeing with our own eyes! It is simply one possible interpretation of the written, pictorial and (rare!) surviving garments from which has developed a representation of clothing of the period which, through being worn at a range of events and while undertaking period activities in a range of weather conditions, has been proved to work – being reasonably comfortable, waterproof and warm, while looking convincing as a fairly standard outfit for the period.

The clothing that we wear for re-enactments and re-creations matters. Beyond the uniform coat colour and pattern that those members who are portraying a military role are required to wear, we have a good degree of choice over our appearance and what we select to wear in our representation of a person from the past. Clothing is also the first thing that the public notice about us as individuals and one of the first things that they are able to compare with their life today. There are countless questions from curious members of the public about what we wear – what it is made of, what it is like to wear, why certain things are worn. The clothing worn by members also affects how we carry ourselves, how we act, and how we under- take activities.

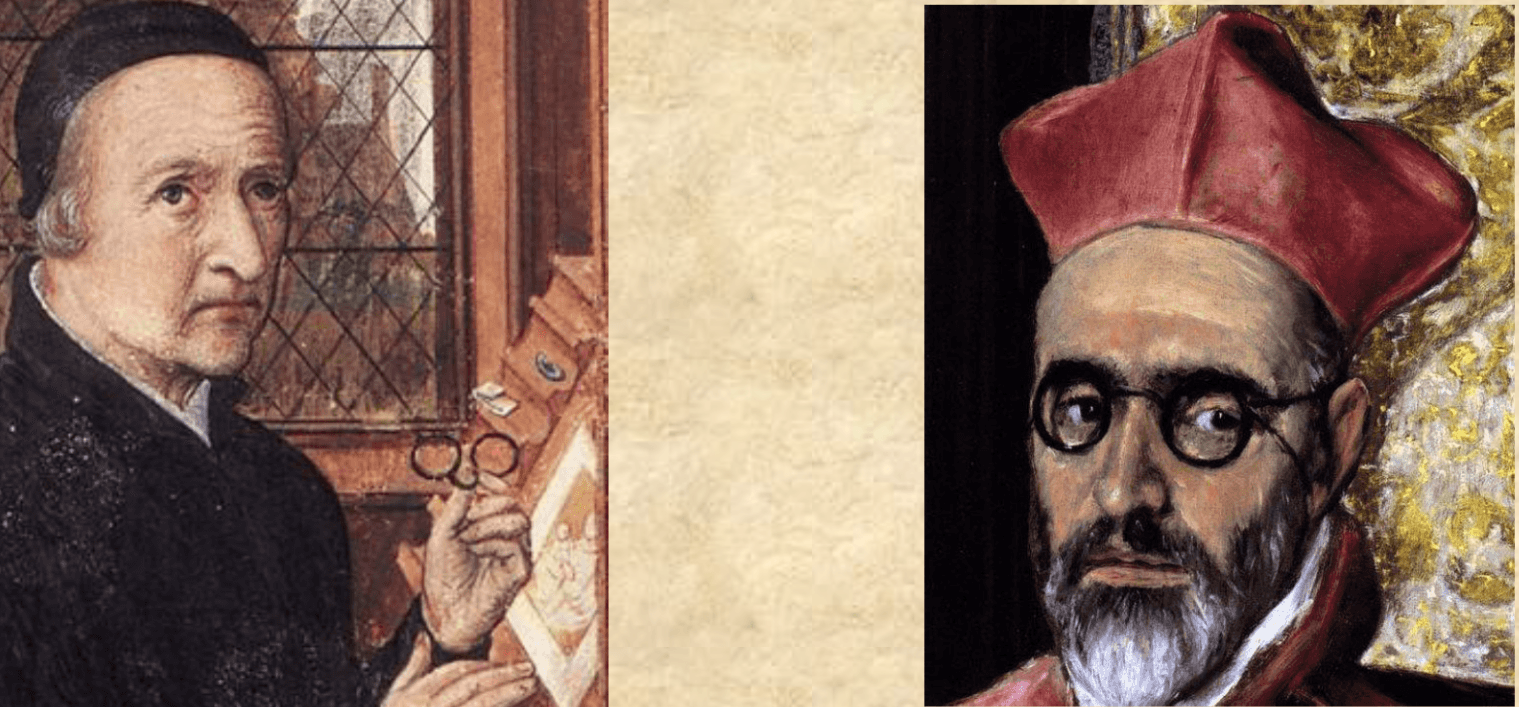

Costume in the re-enactment of the seventeenth century has suffered from a number of fads, fashions and inaccuracies, some of which have survived since the 1960s, some of which have dominated for a few years and then faded away but can still linger in some quarters. However, recent years has seen a growing interest in the development of realistic representations of common clothing. Those with a more academic skill than I have focused on written evidence (wills, inventories and the like), examined a full range of pictorial evidence (wood cuts, illustrations, paintings), and undertaken practical experimentation (making the things to see if they work). This guide is based on much of this research by many others, together with practical personal experience of making and trying out the garments.

Acknowledgements

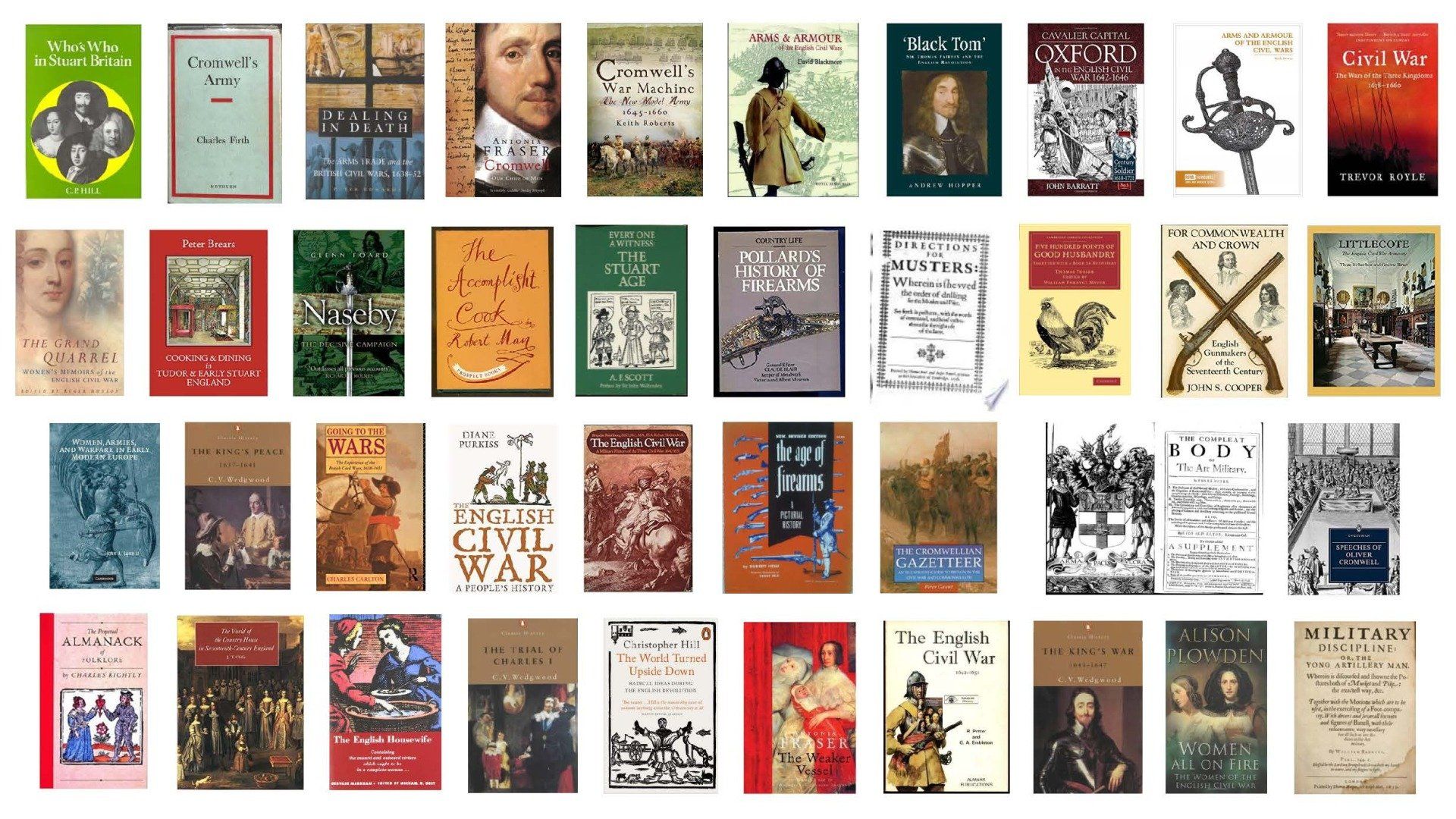

As stated above, this guide draws on the work of those who have undergone extensive research into the clothing of the period. The major sources used for this guide are listed below. Anyone looking for further information on the clothing of the period should explore these texts further. Some of them sit slightly outside our period or deal with the clothing of the wealthy. However they are invaluable as an illustration of the tailor‘s art and give an insight into how garments were cut and constructed.

- Clothes of the Common Man 1580 – 1660 Robert Morris (Stuart Press ISBN 1 85804 162 7)

- Clothes of the Common Man 1580 – 1660 Part 2: Making the Garments Jane Huggett (Stuart Press ISBN 1 85804 180 5)

- Clothes of the Common Woman 1580 – 1660 Robert Morris (Stuart Press ISBN 1 85804 160 0)

- Clothes of the Common Woman 1580 – 1660 Part 2: Making the Garments Jane Huggett (Stuart Press ISBN 1 85804 169 4)

- Children’s Clothing 1580-1660. Jane Huggett. (Stuart Press. ISBN 978-1- 85804 218-3)

A guide to making appropriate clothing for the children on the lower orders.

- Patterns of Fashion: The cut and construction of clothes for men and women c. 1560 – 1620 Janet Arnold (Macmillian Press ISBN 0 333 38284 6)

Deals with upper class clothing slightly earlier than the period. However invaluable as an insight into the work of the tailor.

- Patterns of Fashion 4. Janet Arnold. (Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-57082- 1)

- A study of surviving linen garments from c.1540 - 1660.

Again, a focus on clothing of the upper classes. However, invaluable as a reference for the art of the seamstress.

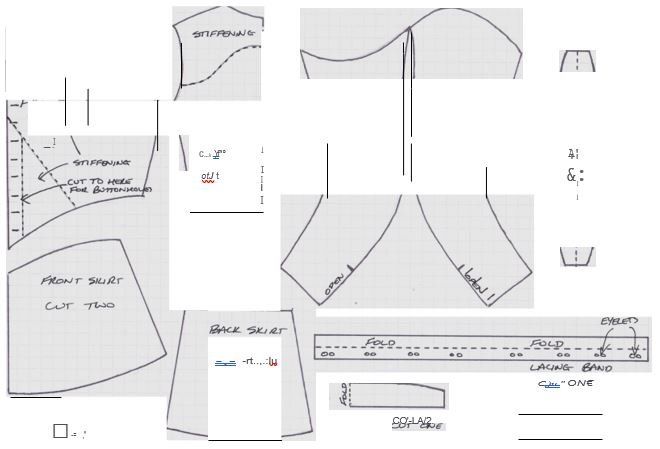

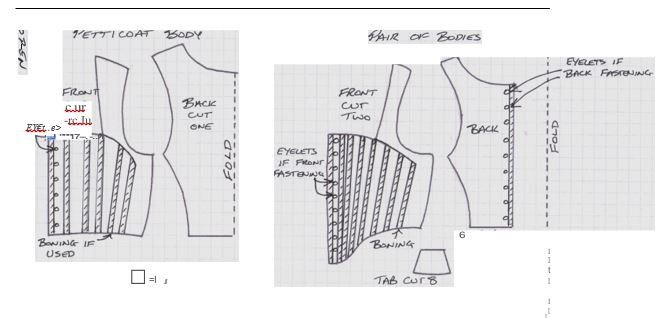

- How to make a Petticote and Bodice of 1580-1660. Gilly Morley. (Stuart Press ISBN 1 85804 244 5)

An easy to follow guide for making these essential basics of women‘s clothing.

- Headwear, Footwear and Trimmings of the Common People 1580- 1660. Robert Morris. (Stuart Press. ISBN 1 85804 170 8)

As the name suggests, this is a useful booklet for those finishing details of a costume - the buttons, the lacings, the fastenings , the hats and so forth.

- Textiles and Materials of the Common Man and Woman 1580-1660. Edited by Stuart Peachey. (Stuart Press. ISBN 1 85804 167 8)

An exploration into the types of fabrics that were used for the clothing of the common people.

- Dyeing the Clothing of the Common People 1580-1660. Peachey and Hopkins. (Stuart Press. ISBN 1 85804 173 2)

A study of dyestuffs and the processes used to dye cloth in the period.

Some websites:

English Civil War (ECW) Living History Resource

Website

http://lhresources.wordpress.com/

How to make and source things Mid 17th Century‖. Many images of clothing of all classes, together with book lists that may prove useful.

Ready to Wear

Website:

http://thegoodwyfe.blogspot.co.uk/

A site with the aim of developing and improving the quality of clothing in the re-enactment of the mid-seventeenth century.

The 1640s Picturebook

Website:

http://the 1642goodwyfe.wordpress.com/

Images from the mid seventeenth century that can act as a guide for clothing.

As with all websites, the quality of the contents cannot always be guaranteed. Browse with care! Devereux’s Regiment are not responsible for the content of such websites.

Appropriate Materials

The materials available to the people of the time really dictate what can be used when recreating the clothing of the period. Modern clothing uses a wide range of materials, both natural and manmade fibres. Today our wardrobes contain cotton, linen, silk, polyester, lycra, nylon, wool, leather, plastic, fake fur – the list goes on. In the seventeenth century, the range of materials was much more limited.

Wool

Wool had been a staple of English trade with the continent since the Middle Ages. It was the basic fabric for much of the outer clothing of the lower orders in the seventeenth century. It was available in range of widths and qualities. Terminology from the period uses a number of different names to describe types of wool, some of the more common being:

- Kersey – Kersey was a narrow, hardwearing fabric with a twill weave (leading to it having diagonal parallel ribs on the surface). It was strongly associated with the clothing of the common people. It was used for stockings, sometimes for doublets and women‘s waistcoats or petticoat skirts.

- Russet – Russet was another narrow fabric (36‖- 48‖ wide or so). Russet was unfinished and came in the colour of the fleece that it was woven from – probably mainly greys and browns. It was strongly associated with the clothing of the common people, particularly in the countryside. It seems to have been used for doublets, women‘s waistcoats, britches and petticoat skirts.

- Broadcloths – Broadcloths were just that – cloths that were broad! They would typically be woven on a loom that produced cloth that was up to 60‖ wide, sometimes wider. Broadcloths came in a range of qualities depending on the finish. The smoother and more finished the fabric, the more expensive it would be. Broadcloths were used for better quality clothing, gowns, coats etc. It was often used for soldiers‘ coats in Civil War as it was hard wearing and waterproof.

- Flannels – Flannels were lightweight wools that were sometimes used for children‘s clothing and used for linings of adult garments.

- Cottons – Cottons in the seventeenth century have very little to do with the cotton plant! Cottons were narrow wools (36‖-48‖ wide) and fairly lightweight. They were finished so that they had a slightly fluffy surface – this process being called 'cottoning'. Cottons were used for linings of outer garments and also were a good fabric for children‘s clothes.

- Frieze – Frieze was a very thick, heavy woollen fabric made from fleeces that were of poorer quality. Looking quite hairy in finish, frieze was used for thick coats, jerkins and gowns for winter warmth.

- Worsteds – Worsteds were wools woven with twisted yarns. They were very hard wearing fabrics used for gowns, doublets and some- times aprons.

- Bays – a loose weave woollen fabric. Often used as a lining material.

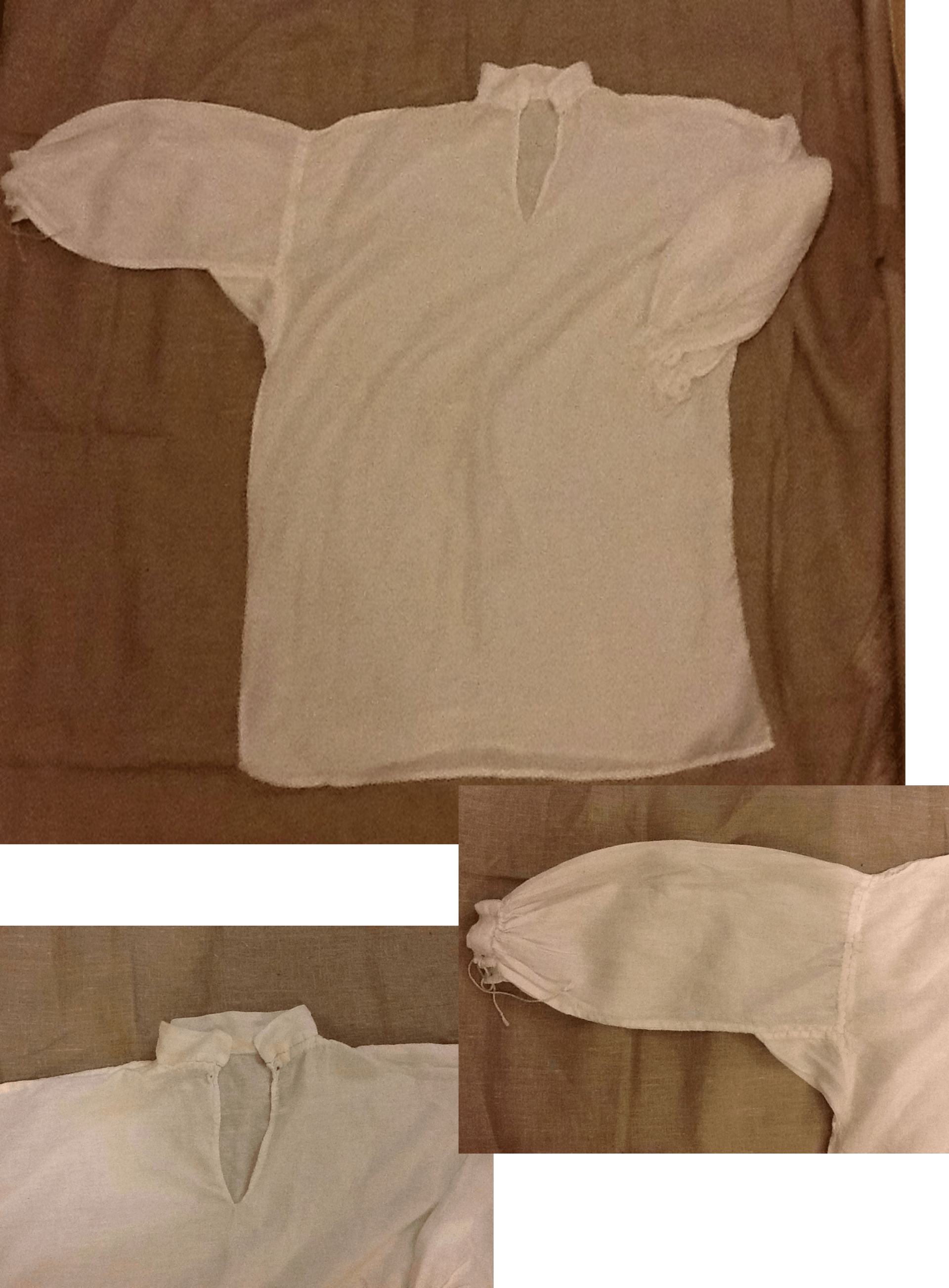

Linen

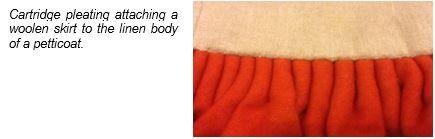

Linen is a thin material made from the long fibres of the flax plant. Some was produced domestically, but a large amount was imported from Scot- land or the continent. Linen was used for underwear and as a lining material. Thicker linen canvas was used to interface other fabrics in garments like doublets and women‘s waistcoats, or even as the outer material for these as lighter weight summer wear. It can be used as basis for petticoat bodies to provide stiffness and support. As such it could be lined with thinner linen and attached to a linen or woollen outer. Thinner linens would be used for collars and coifs. As with wool, the finer and more finished the fabric, the more expensive it would be. The very thinnest linens (often called lawns) were almost transparent at times and would be used for collars and cuffs by the wealthy. Bleaching linen prior to sale would have added to the cost, but white linen does seem to have been the norm for underwear. However, natural (light brown through to silver grey) linen was probably also used for this purpose and often becomes bleached through the laundering process. Some linens may have been dyed for use as lining materials. References (written or visual) to coloured linen being used for shirts and smocks are rare and are often linked to the upper classes (many pre- dating the period that we are representing). Some references exist to collars being starched in light blue or yellow dyed starch to extend their life once they had been worn for a long time and had become ingrained with dirt, or to keep up with some fashion. However this seems to have been a limited practice for those with wealth enough to keep at the cutting edge of fashion. To represent the ordinary person, white or off white linens are more appropriate for the underwear layer.

Leather

Leather as a clothing material was quite widespread in the seventeenth century. It would be naturally tanned – chrome tanning was not used until later. It could be dyed with natural dyes (reds, yellows and yellow-greens are easily obtainable), but this added to the cost and may have been limited to purses and thin belts. Leather was used for shoes and boots. Jerkins, worn over doublets to protect them during hard work, do survive, along with references to doublets and britches being made from leather. It was also used for thick buff coats, worn for protection from sword cuts by officers or the wealthy. A favourite re-enactment fallacy has lasted from the 1960s that common soldiers wore these. Cavalry troopers are recorded as wearing them, and there are some references to members of the London Trained Bands having them, but there does not seem to have been a mass issue to the armies of the time. The fact is that buff coats were made of highly expensive thick hides, often treated with ochre to give them a yellow colour. The cost was beyond the pocket of ordinary people and too expensive to waste on the cannon fodder of the army. The buff coats available from most re-enactor traders bear little resemblance to the real thing.

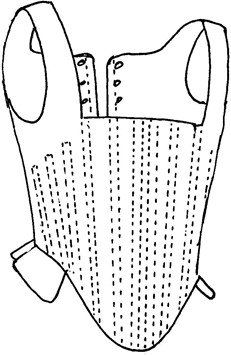

For women, there has been a recent re-enactment fashion for thick leather corsets, often worn without an over garment, citing a few references to leather bodies being made for wealthy women. The leather bodies that are referred to have thin soft leather outers, decorated with stamped patterns, while the stiffness of the garment is provided by whalebone or reeds. They survive from the wardrobes of the wealthy and probably would not be replicated further down the social scale. Such thick leather corsets are best avoided.

Silk

Silk in large quantities would be beyond the pocket of most common people. Some references to small silk items do turn up in wills and inventories for common people. It is best to treat these almost as family heirlooms, as second hand clothes, or as remarkable items worthy of special mention. It is best to avoid silk unless you are making a garment of the upper orders.

Mixed Fibres

A few examples of mixed fabrics exist in the period. Fustian was one fabric of period that may have had cotton as we know it as one of the fibres. Fustians had a cotton or wool weft and linen or wool warp. They could be used for doublets, gowns, or for lining other fabrics.

Decorative braiding

As with lace, braids and cords were used to decorate the clothing of wealthy. Just like lace it took time and money to create, therefore it would be a sign of wealth and status. Braids and cords may have been removed from the clothes of the better sort before they found their way on to the second hand market. Braids in the seventeenth century would often be made from silk and threads made from silver and gold – all expensive materials. Some may have found its way in to the possession of the lower orders, through the second hand market or as short lengths purchased from the petty chapmen (travelling purveyors of trinkets, buttons, small amounts of trimmings and lace and so forth). However, as with lace, finding appropriate period braids or cords can be difficult. Modern machine made braid is broadly inappropriate for the period and is best avoided. Woollen and linen tapes can be found, but caution is needed as some tapes and braids are, again, not suitable for the period. If in doubt, don‘t buy! Having plain clothing in appropriate colours and made using appropriate materials and pat- terns is better than then using obviously modern, incorrect braid and trimmings.

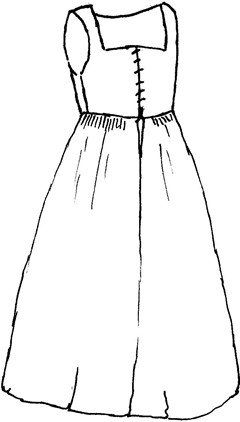

Women—What did they wear?